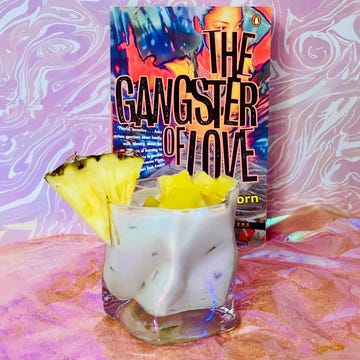

Jimi Hendrix died the year the ship that brought us from Manila docked in San Francisco. My brother, Voltaire, and I wept when we read about it in the papers, but it was Voltaire who was truly devastated. Hendrix had been his idol. In homage to Jimi, Voltaire had learned how to play electric guitar, although he’d be the first to admit he wasn’t musically gifted. “It’s okay for me to dream, isn’t it?” He’d laugh. Voltaire grew his bushy hair out and teased it into what he called a “Filipino Afro.” Voltaire caused a sensation whenever he appeared in his royal purple bell-bottoms and gauzy shirts from India. My parents were appalled, especially when Voltaire took the next logical step and adopted an “indigenous Filipino” hippie look. The crushed velvet was replaced by batik fabric; the corny peace medallions replaced by carabao horn, scapulars, and amulets he purchased from bemused market vendors in front of Baclaran Church.

My father once threatened to have Voltaire arrested by the Marcos secret police for looking like an effeminate bakla. Then there was the incident of Voltaire’s guitar, which he set fire to in a very public ritual in Luneta Park. According to my father, Voltaire was on the military’s growing shitlist of subversives and hippie dissidents. Nothing much came of my father’s threats, except after one of their more physical confrontations when Voltaire disappeared for weeks. My mother was sure he was dead. “He’s probably holed up in some Ermita drug den,” my father scoffed, though he was plainly worried. Voltaire eventually showed up without explaining himself, but by then no one cared: my mother’s announcement that she was finally leaving my father overshadowed everything.

Voltaire and I convinced ourselves that our parents’ breakup was temporary, that the journey we were taking with our mother was some sort of weird vacation. Our lives as the children of Milagros Rivera had often consisted of startling events and irreversible showdowns. We were relieved to be away from the Philippines after the bang-bang, shoot-’em up elections. Who gave a damn about voting anyway? Even my father was forced to admit that the elections were a joke. Everyone knew Crocodile had fixed it to win. That’s what Voltaire called Marcos now—Crocodile. Imelda was Mrs. Croc, or Croc of Shit, as Voltaire sometimes said when he was in a truly bitchy mood. Voltaire blamed Marcos, the CIA, and the Catholic Church for everything that was wrong with our country. He once said the CIA had contaminated the Pasig River with LSD as part of their ongoing chemical warfare experiments against the Vietcong. He also claimed that we were the original gooks. He and our sister, Luz, the eldest, used to argue about politics all the time. “Didn’t you know the term gook originated in the Philippine-American war?” he once yelled at her. “Enough!” Luz yelled back at Voltaire.

Excited and distracted by our sudden trip to America, we didn’t dare ask too many questions—even when Luz stubbornly refused to leave Manila and my father.

Voltaire croons softly to himself as he leans over the deck railing and studies the faces of the motley crowd waiting on the pier. “‘Purple Haze was in my brain, lately things don’t seem the same…’ There she is!” He waves to a tiny woman bundled up like an Eskimo in a hooded down parka and pants. Voltaire must’ve recognized Auntie Fely from those Kodak cards she sends every Christmas with photos of her with her stepchildren and husband stiffly posed under a lavishly decorated artificial tree and “Merry Xmas & a Happy New Year to You & Yours from the Cruz Family” embossed in gold.

According to my brother, I was three when Auntie Fely left to find work in America. A few years older than my mother, Auntie Fely was unmarried then, and she doted on all of us. She stopped by our house on her way to the airport for one last teary goodbye, though family and friends had already bid their farewells at numerous ceremonial breakfasts, lunches, meriendas, and dinners held a month before my aunt’s scheduled departure. Luz was the first to receive kisses and hugs, then Voltaire. My aunt gave each of them envelopes stuffed with peso bills. “Don’t spend it all on sweets.” Because I’m the baby of the family, Auntie Fely saved me for last. She scooped me up with her strong arms and peered into my face as if to memorize it. The intensity of her gaze, magnified through Coke-bottle eyeglasses, frightened me.•

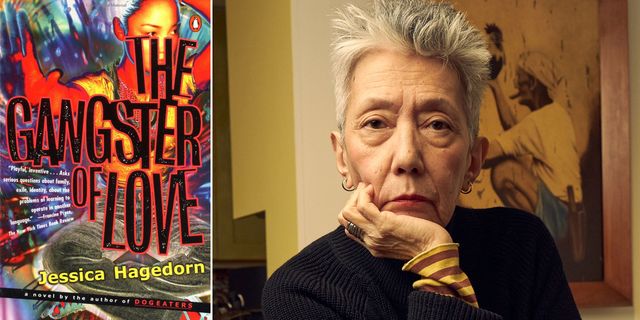

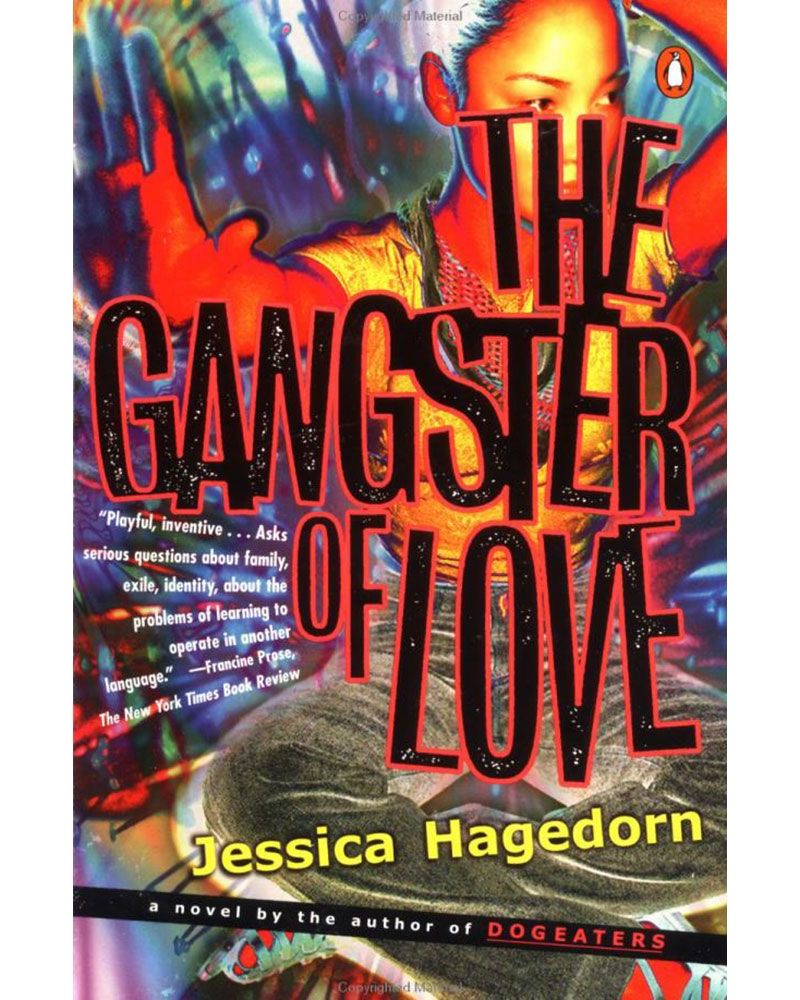

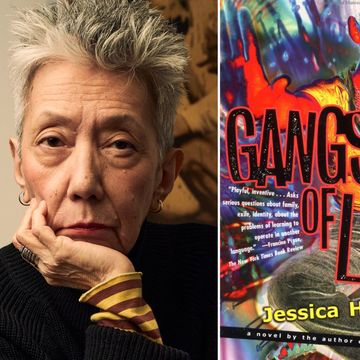

From The Gangster of Love, by Jessica Hagedorn. Reprinted by permission of Jessica Hagedorn and Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyright © 1996 by Jessica Hagedorn.

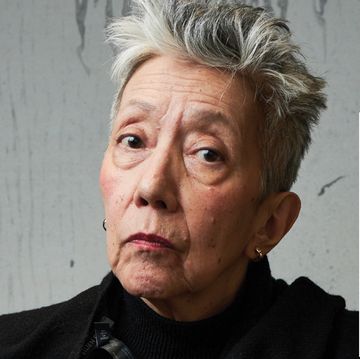

Jessica Hagedorn was born and raised in the Philippines and came to the United States in her early teens. Her novels include Toxicology, Dream Jungle, The Gangster of Love, and Dogeaters, which received an American Book Award and was a finalist for a National Book Award. She is presently at work on a hybrid memoir.