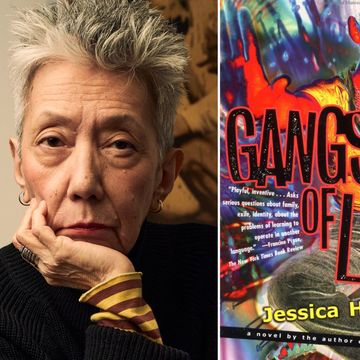

Deep into Jessica Hagedorn’s boisterous 1996 masterpiece, The Gangster of Love, our heroine, Rocky Rivera, has moved to New York to make a go at the rock and roll life. It’s the late 1970s, the peak years of CBGB. Rocky’s band, which gives the book its title, gigs a lot but doesn’t earn much. One night, Rocky jumps in a taxi to head back down to the Lower East Side. It’s late; the cabby gives her the eye in his rearview mirror. Rocky knows it’s wise to be deferential. She doesn’t need the hassle; she ought to call him sir. A fizz or rage bubbles, though, and she tells us, “My father, I want to tell this cabdriver named Eduardo Zuniga, was so respected that he had no name in the Philippines. Everyone just called him ‘Sir.’ I also want to say: Eduardo Zuniga is a poet’s name. But I don’t.”

So much unfurls in interactions like this in The Gangster of Love, one of the most perceptive novels ever written about love and shame. How these two emotions live side by side in the heart. Pumping in tandem, creating a tension in the blood. Come closer, escape. Recognize kin, put them down. As a poet and musician, Rocky externalizes this torque in her poems, in her songs, and in the bohemian life she lives with fabulous abandon. She takes lovers. She sets up a life on her own terms. Her family, however, don’t get this second life, and this explosive, beautiful book shows the pain that costs them—and Rocky in the reverberation.

It’s a small book but feels much bigger, owing to its structure. The novel swirls from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s in a vivid montage of brilliant set pieces and moving character sketches of Rocky’s family. We meet them first at ground zero, when Rocky; her mother, Milagros; and her brother, Voltaire, land flat on their backs in San Francisco after her parents’ marriage fell apart and her father left them in Manila. It’s the early 1970s, San Francisco is mayhem, and arrival is hard. Milagros, though a force, is in the years of fading beauty; Voltaire has the beginnings of a mental illness, and Rocky is brilliant but prideful, decadent, and needs relief from her chaotic house.

Like so many sensitive kids who feel smothered at home, Rocky escapes by going out. Is there a better book on San Francisco nightlife in the 1970s? In many ways, The Gangster of Love feels like an update to Jack Kerouac’s The Subterraneans, without the spin of exoticism. Instead of Mardou Fox, Hagedorn gives us Keiko Van Heller, an artist and muse who is Dutch or Hawaiian or Cuban, depending on which day you ask. Men fall for her, women, and in her own way, Rocky does too. Keiko’s genius for self-invention is the doorway through which Keiko walks into a bigger life.

So is Elvis Chang’s. Sexy, silent, and sometimes a good musician, Elvis seduces Rocky and quickly gives her the clap. These were the last days when any venereal disease could be treated with penicillin or the like. Already, Rocky hears whispers of something much worse happening to gay men. She refuses to be proprietary about Elvis, who tries to make her jealous and fails. Instead, Rocky falls deeper and deeper into the spell of Keiko. When Keiko and her partner skedaddle to New York, Rocky abruptly decides to go, too, with Elvis.

Shuttling from San Francisco to New York in the 1970s, The Gangster of Love could be the kind of book that works, owing to its borrowed scenery. To having been there and escaped alive. This isn’t the case. All the energy in the book pours from the pump house of Hagedorn’s prose. Her syntax is gritty, musical, rhythmic, and aural. You don’t read this book so much as ride it like a wave. It jolts you with its prose power, its gum-stuck, coke-headed surges of hilarity. Half the book is dialogue, and it’s brilliant. Arguments. Monologues. And then in the later half, the novel itself becomes a play as Rocky the musician turns into Rocky the playwright, casting Milagros to play herself in theater about their lives.

One can hardly blame Rocky for making use of what fate gave her. From the moment Milagros walks into this book, she threatens to make it hers. Dramatic, beautiful, a skilled manipulator, but also loyal and loving, she is the critical mass creating emotional gravity here. When Rocky moves to New York City, as Hagedorn did herself in the 1970s, you know that the distance from her mother is going to be hard. That for all the nights New York acts exactly as Rocky had hoped, she is going to miss her mother. And she does, in her way.

It doesn’t hurt that making people love her is one of her mother’s greatest skills—especially men. One of the book’s ongoing melodies is the parade of men who come to the house to eat Milagros’s cooking and eventually do her bidding. That includes her landlord, her banker, and, to a smaller degree, her son. Rocky, however, refuses to bend, totally, and Hagedorn brilliantly reveals how much love and tenderness exists within the barbed force of that tension. They are not at war; they are simply entwined, perhaps more than Rocky at first realizes.

Hagedorn was a poet first, then a playwright, and you can see how she deploys her skills in each form of literature within this novel. While Milagros looms large, she doesn’t dominate the stage. We also get closer glimpses at Rocky’s dreamy, troubled brother and her father’s brother Marlon, who lives in Los Angeles next door to an aging Filipina movie star, tending to the needs of her ego and her army of cats with courtly care.

Marlon is just one of many characters Hagedorn passes the narrative to briefly, so we hear from him directly. It feels on the page as if he is stepping forward into a spotlight for a monologue. When Marlon falls ill, for example, we get an extraordinary passage of him trying to imagine how to spend the rest of his days. Later, when Rocky gets pregnant, a second time, her mother comes to New York City to help with the baby, and we see Rocky’s life from her mother’s eyes. What might have come across to Rocky as a mask of judgment is in fact concern and care.

These emotional depths also open up the rest of the cast. One of the book’s most heartbreaking scenes involves a family dinner that Elvis allows Rocky to attend when his family comes to New York. His parents own a Chinese restaurant in Oakland, and they have brought Elvis’s high-achieving student brother to taste the sights of New York, a tax write-off given their business. Rocky and Elvis are broken up, and yet she’s harassing him under the table, groping his dick, saying the right words to his parents but torturing their son, who begins to act out. The way the meal devolves into tears is real and unforgettable.

These are just the main characters, too. The Gangster of Love teems with a secondary cast, from the band’s creepy, vulgar drummer, Sly, to Dr. Sandy, the acupuncturist who gives Rocky a job so she can pursue her dreams. Introduced by Marlon, Rocky manages to make this work stick, where waitressing and other menial jobs bore her. In part because Dr. Sandy actually cares for her, Rocky’s not there to take anything. Or have it taken from her.

“On one of my visits back to San Francisco,” Rocky says at one point, “my mother asks me why I try so hard to be a man. ‘Look at your Grandpa Baby. So-called inventor of the yo-yo. And what did that get him?’ She blames it all on coming to America. Grandpa Baby was a renowned wood-carver in his hometown back in the Philippines, but he gave it all up to come to California. First he broke his back picking asparagus in the fields, then he worked as a bellhop in some hotel in Santa Monica, where he ended up whittling a yo-yo and starting his own company. The rest, as they say in my cynical family, is the same old shit history. Grandpa Baby sold his rights to the yo-yo for a lousy thirty thousand dollars.”

Part of Rocky’s search in the novel is a quest to make her way in the world without being made a sucker. How to be called sir, even if it means playacting across gender roles. How refreshing and beautiful it is to read a book that is almost 30 years old that is actually ahead of its time. In the most enlarging way, The Gangster of Love is a novel about queer love and about the world Rocky builds to make the getting of it and the holding on to it possible.

At one point, the band on the rocks, Elvis and Sly at their worst, Rocky and Keiko go to bed together. “Here I am, Keiko,” Rocky thinks, joking, stripping off her clothes. She’s alarmed at how she doesn’t feel anything as Keiko begins to touch her. In the end, they have sex and wind up spooning and holding each other and that’s that.

Milagros slightly gets it wrong, then, when she tells her daughter that she’s acting like a man: Rocky is acting the way Milagros thinks men act, running away for things, for fortune. But rather than stake her claim on a toy, Rocky has placed her bet on art and love. She is going to take it all, rather than have it taken from her, which makes her an unruly character to follow. Sometimes amoral. The way she proceeds drives her further and further away from her family and the past, until suddenly it snaps back.

The Gangster of Love isn’t just the name of Rocky’s band. It’s a title that can apply to several characters within the novel. First and foremost, Rocky, as she barrels into this relationship or that, determined to make it out without getting hurt. Her mother also has a claim to that title, for she is a gangster who needs all love to flow up toward her. Ultimately, it might also apply to Rocky’s baby, Venus, who, when she is born, reorders the laws of the universe as to who matters and why.

It is a minor miracle that Hagedorn manages to make such a deeply cool book about rock and roll and bohemian life and also such a warm and real book about family—about actual and chosen family. As everyone knows, throughout his life, Kerouac went home to his mother’s to write about the chosen family he sometimes drove to distraction. Here, the mothers haven’t been edited from the book. They are everywhere, and in many ways, the song Hagedorn sings so beautifully is theirs.•

Join us on April 18 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when Hagedorn will appear in conversation with CBC host John Freeman and special guest Sean San José to discuss The Gangster of Love. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

John Freeman is the host of the California Book Club and the editor of Freeman’s, the final theme of which is Conclusions, out this fall. He is the editor of The Penguin Book of the Modern American Short Story and Freeman’s and an executive editor at Knopf. His latest book is Wind, Trees. He lives in New York.