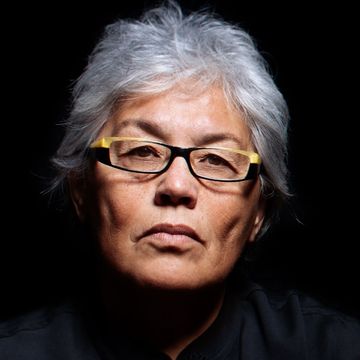

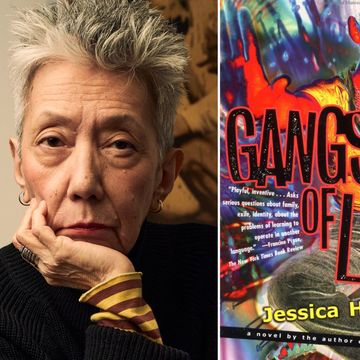

John Freeman told the California Book Club audience at the top of the hour that he’d recently gone to a Brooklyn event to celebrate Reading the Room: A Bookseller’s Tale, by Paul Yamazaki, the principal book buyer at City Lights Bookstore. When Freeman asked Yamazaki about the relationship between booksellers and their customers who became writers, he cited this month’s California Book Club author, Jessica Hagedorn, as one such author. Hagedorn had turned around from the front row and said, “Wait a minute, I’m here.” Freeman said, “Everywhere I’ve turned in the last 30 years of my artistic life as a reader, as a person who cares about poetry and performance, whenever you go into a gallery space, it seems like Jessica Hagedorn has changed it and altered it for the better.”

Freeman described Hagedorn’s artistic life as a study in collaborations with other poets, writers, musicians. The Gangster of Love opens with the protagonist, Rocky, arriving in San Francisco. He asked Hagedorn to talk about coming from Manila to San Francisco. Hagedorn responded, “It was as if my mind was blown from the moment I stepped off that boat—ship.” She said it took almost 20 days to arrive, but it was helpful to go slow. “We were just shell-shocked...and shell-shocked by what had happened to our world. The lost world. It was very complicated and messy. The city felt alive to me, and I couldn’t help but sort of try and soak it all in, even though I was upset.”

Even before the poet Kenneth Rexroth brought her to City Lights to go to a reading, her family had been living in a flat near the panhandle that was close to many secondhand bookstores, which she’d wander into. “I just loved it,” she said. “I’ve always known I wanted to be a writer, as a little child. So the idea that there were these books in the bins for 25 cents...I would just buy stuff.” Various things, like the cover or having heard of a Beatnik writer who was “a little bit taboo and delicious,” would make her take notice of a book and buy it and copy it. She added, “You know, that’s how you learn how to write. Stealing from the greats, or the not so great.”

Freeman asked how Hagedorn developed a distinct voice. “You clearly had an inner voice that wanted to come out and wanted to speak...but when did it become an outer voice?... When did you feel OK saying, ‘I’m going to stand up. I’m going to read this poem’?” Hagedorn explained that in the early ’70s, she fell in with “this great nomadic tribe of poets who were much older than me and who shared a lot of things with me and were very generous about asking me to read” with them. She learned through trial by fire in San Francisco, where she knew from the audience’s reaction whether they didn’t like something. She also wound up studying at the American Conservatory Theater to learn more about performance.

Freeman pointed out that the friendship between the characters Keiko and Rocky is “one of the molten cores of this book.” Hagedorn said that she was fortunate that those moments in the ’70s in San Francisco were so dynamic. “There was so much going on in the Bay Area that was creative, that was dangerous, that was gorgeous, that was very exciting.” The Bay Area audiences, she said, were generous. The city nurtured her, as did the artists who were ahead of her. Keiko was a composite of several amazing women she’d known who’d goaded her and encouraged her and told her to just do it.

Later, Hagedorn and special guest Sean San José, the artistic director of the Magic Theatre, discussed adapting written words to the stage. “It isn’t merely dialogue.... It also can become living literature,” he said. For performance people, he said, it’s thrilling to be able to do “deep, heavy, dense rhythmic multilingual text onstage.... I mean, that’s what our cities really are.” He and Hagedorn together read a scene involving the character Carabao Kid, who was inspired in part by activist and poet Al Robles.

San José commented that he works with a lot of writers who aren’t held down by genre, saying that “they reveal our humanity or interior battle to find our humanity in a way that, on the page, can be very one-on-one and contained, but when you’re forced to share it, in front of an audience, it becomes...it can be transformative.”

Hagedorn agreed, “I love hearing the performers transform what I write and show me something else. It’s gorgeous.”

An audience member asked Hagedorn if she had ever feared not being Asian enough in her writing and, if so, how she overcame those fears. Hagedorn said that she questioned herself sometimes because people put things on her, particularly when Dogeaters came out. “I tried to own it as much as I could. They hadn’t even read the book but had only looked at the title. But it was there to provoke, so I had to own that. But the thing about representing who you are...I’m not going to apologize for anything.” She advised, “Don’t worry about it. Just write who you are, and it’ll be fine. Do it well. Stand by your gut, dammit. It pains me to hear it—the fear. It’s so hard to be an artist if you’re afraid like that, so you have to just really get through it.”•

Join us on May 16 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when distinguished panelists Robert Hass, Brenda Hillman, Jack Shoemaker, Rick Bass, Jane Hirshfield, Will Hearst, Kim Shuck, and Tongo Eisen-Martin will appear in conversation with California Book Club host John Freeman and Gary Snyder, making an appearance, to discuss and celebrate Snyder’s books Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems and The Practice of the Wild. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.