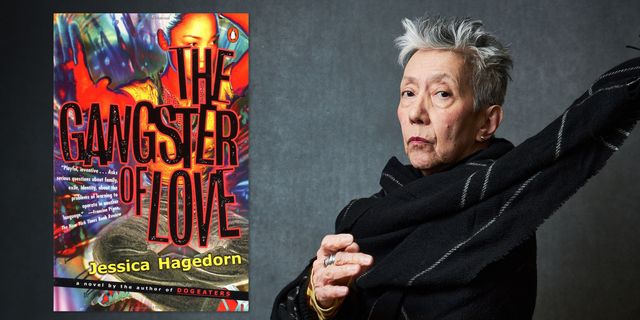

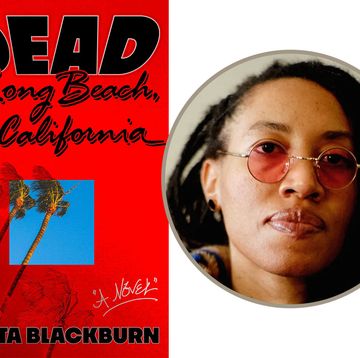

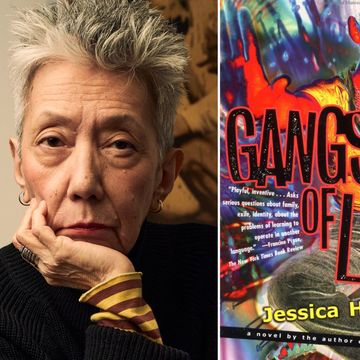

Jessica Hagedorn’s fiercely exuberant 1996 novel, The Gangster of Love, hurtles through a kaleidoscope of tones, mixing eruptions of imagination with elements from her lived experience as an immigrant child and then as a punk rock musician in 1980s New York. Hagedorn—novelist, playwright, musician, and multimedia performer—is, most of all, a collagist, including in her earlier novel, the American Book Award–winning Dogeaters, a marvelous cacophony of voices and modes set in Manila.

The Gangster of Love is also a collage, united by a panther-like omniscient narrator who roves across the book, offering knowing, witty, and sometimes mournful observations and orchestrating a variety of points of view, most often that of Rocky Rivera, the protagonist of the book. The narrator plunges us into a poetic examination of love, ghosts, betrayal, and gossip before introducing the Rivera family, who, splintered by divorce, move from Manila to San Francisco the year that Jimi Hendrix dies. “There are rumors,” the book begins. “Surrealities. Malacañang Palace slowly sinking into the fetid Pasig River, haunted by unhappy ghosts. Female ghosts. Infant ghosts. What is love? A young girl asks.”

The jagged, self-destructive spirit of Hendrix presides over the book. He drops in via short dream plays to give Rocky and her boyfriend a reality check. (“Thought I was a mystic, thought I was blessed,” he says. “Thought that was enough.”). His presence is meaningful not only for Rocky, who becomes a punk musician, but also for Voltaire, Rocky’s beloved, demon-ridden brother. Their prickly, glamorous, critical mother, Milagros, runs her own catering company, Lumpia X-Press, cooking brilliantly and dazzling customers. Marlon, Rocky’s charming, queer dancer-choreographer uncle, is as mortal and vulnerable as anyone else Rocky turns to for advice, comfort, and a sense of how to live. All these characters judge, tell on, look after, and betray the others.

Rocky grows up and into a life as a struggling artist with turbulent love affairs and dangerous friendships. She fights with her mother and falls in and out of love, including with Elvis Chang, a smart, coldhearted alley cat guitarist who understands what it means to be pulled between two cultures. She comes under the sway of charismatic photographer Keiko Van Heller, who lies to her, introduces her to drugs, and seduces her into a reckless version of an artist’s life.

Collages of imagery and tonal shifts illuminate Rocky’s tensions and inner conflicts. When a drunken Rocky and Keiko finally consummate their erotic, competitive relationship, Rocky feels only numbness, anger, and resistance. Afterward, she lets her imagination “run wild” in a vision of “hermaphrodite angels with bronze skin floating alongside the naked, bleeding perfection of my tormented Saint Sebastian”:

Arrows pierce his bony ribs as he arches his back in anguish. In my dream, Tagalog is not spoken, nor English, nor Spanish. The silence of penance prevails. My perverse angels ascend before disappearing into the cotton ball clouds of heaven. Orgasmic bubbles burst in my vast, baby blue void. A hundred more arrows sail through the air. Whoosh. Flames erupt from a gaping, aubergine mouth. Saint Sebastian rolls back his eyes in ecstasy.

My mother’s right. I am just like everyone else in my family. I believe in heaven and hell, the pleasures of denial, and the rewards of sin. I want to tell Keiko the truth. “I enjoy this only because it’s forbidden.”

In this juxtaposition of poetic, alliterative, violent imagery with a straightforward, declarative realization of vulnerability, the erotic becomes anguish, a piercing by arrows. Dream collides with reality, insight, self-awareness. The “silence of penance” suggests that no language is possible in this vision of ecstatic slaughter and release. When Rocky reveals to the reader that she knows Keiko sneaked into another character’s room that morning, her anger and resistance make sense in a new way. The switch in voice, followed by a revelation of context, creates a gorgeous, painful, fascinating imbalance.

Throughout all the characters’ adventures and catastrophes, the restless narrator’s mature perspective holds the book together. A story of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll could fall into gritty sentimentality. A collage can feel arbitrary, a pointless display of virtuosity. Hagedorn, however, makes us feel the necessity of a splintered view of an immigrant artist’s life, how it can never be wedged into a tidy, linear narrative. The book is preoccupied with self-delusion, visions, and dreams, but only in the context of a ruthless commitment to truth and a sense of how much remorse can cling to even the most inevitable losses.

This understanding deepens The Gangster of Love, creating a beautiful, anguished counterpoint to the vivid, inventive, sometimes violent stories of the characters’ misadventures in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York. Hagedorn’s parents, and other friends and family members, died while she was writing The Gangster of Love. The spiky interactions between Rocky and Milagros, the long postponing of a visit to the Philippines to visit her sick father, all feel tinged with regret, the remembrance of rage and perplexity, the sense of time and opportunity lost. Rocky’s yearning for the sordid glamour of raw experiences and stardom evolves into the tenderness and frustrations of caregiving, of what it is to be daughter, sister, friend, lover, niece, and mother, while still holding on to the dream of making art.•

Join us on April 18 at 5 p.m., when Hagedorn will appear in conversation with California Book Club host John Freeman to discuss The Gangster of Love. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

Sarah Stone is the author or coauthor of four books, including the novel Hungry Ghost Theater and (with Ron Nyren) Deepening Fiction: A Practical Guide for Intermediate and Advanced Writers.