Let’s flash back to 1973. I am living in San Francisco. It is a glorious and heady time—the shaky transition out of the burned-out ’60s. Things are uncertain and, therefore, exciting.... Defiant, naive, and passionate, we are sprouting up all over the Bay Area—artists of color who write, perform, and collaborate with others, borders be damned.”

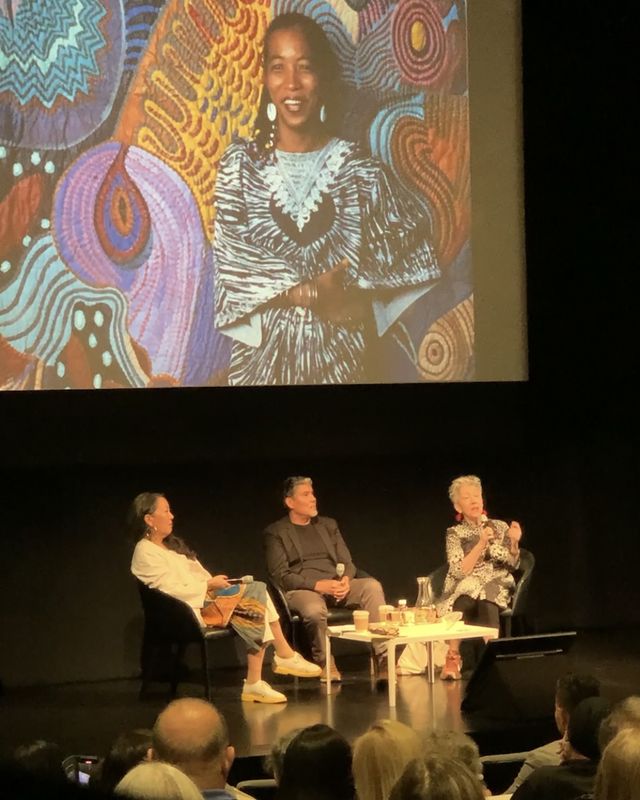

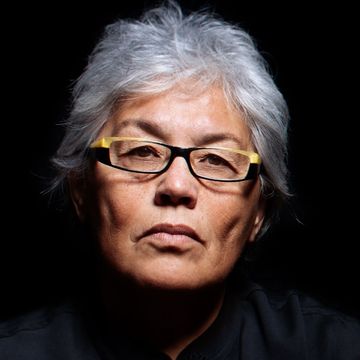

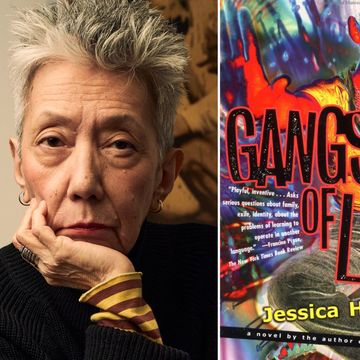

This is how Jessica Hagedorn began her remarks at a panel held last autumn at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in connection with a retrospective of paintings by Filipino American artist Pacita Abad, who lived for a brief time in the Bay Area in the early ’70s. Her words were drawn from her introduction to Danger and Beauty, a book of poetry and prose, but directed toward Abad, now deceased. She didn’t deliver the opening commentary herself—she had lost her voice in the morning, prior to the event, and so Sean San José, artistic director of the Magic Theater and cofounder of Campo Santo, delivered her initial address.

Hagedorn, Filipino American artist Paul Pfeiffer, and moderator Eungie Joo, the curator and head of contemporary art at the SFMOMA, discussed San Francisco in the 1970s and ’80s “as a nexus of cultural activity for international and diasporic artists like Abad.”

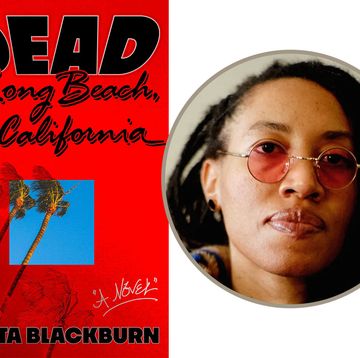

Recipient of the Rome Prize for Literature and a Guggenheim Fellow, Hagedorn has returned to the Bay Area many times. In 1993, she appeared in the Berkeley Rep’s Airport Music, collaborating with writer-performer Han Ong. Her novel The Gangster of Love was adapted into a play about the multicultural firmament of the ’70s, a time when artistic activism swept the Bay Area. Directed by Loretta Greco, it premiered at the Magic Theater in 2018.

But the 2023 panel at the SFMOMA was Hagedorn’s true homecoming, as hundreds, including a large contingent of Filipino Americans, turned out to celebrate the hometown girl who made good. Taking the contemporary audience back to 1970s San Francisco, she mused that it “seems to be a city of musicians and poets more than anything else.” Among others, she shouted out the late Al Robles, Ntozake Shange, and myself, saying, “They were my teachers and peers, kindred spirits, borders be damned.”

Hagedorn’s words returned me to a period when collaboration across racial class and ethnic lines produced poetry, painting, and music that initiated a new direction in American culture. The direct antecedents of these collaborations were the Black Arts movement of the 1960s and the Beat movement. Black men dominated Black Arts, and the movement found its seeds in the creativity of other Black artists and eloquent authors who had challenged traditional white aesthetics. The Beats were primarily white males.

But in 1970s San Francisco, artists mixed it up. Women were catapulted to the forefront. In Women of the Beat Generation, edited by Brenda Knight, Anne Waldman excoriated the patriarchal avant-garde for thwarting the advancement of female artists—female Beats emerged from the shadows.

Meanwhile, friends Hagedorn, Shange, and Thulani Davis performed together as the Satin Sisters at bars like Minnie’s Can Do, where Shange’s classic choreopoem for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf was workshopped before its ultimate Broadway destiny and fame. The late poet and novelist Al Young and I were the first to publish an excerpt of for colored girls in our magazine, Yardbird Reader. We also published Hagedorn and Davis. The Satin Sisters’ art was focused on intimacies and solidarities between African American and Asian women.

And back then, artistic and literary events happened all over town. At the panel, Hagedorn vividly described how writers navigated the San Francisco poetry scene. “You could be at the Longshoreman’s Hall, where you might read with Allen Ginsberg and Ken Kesey, then move on from there and read with Roberto Vargas at Glide Church. He ran off with the Sandinistas.”

The trio stayed intact when they left for New York in the late 1970s. They performed in Where the Mississippi Meets the Amazon, a poetry piece with live music by David Murray and Anthony Davis. Directed by Oz Scott, it was presented at the Public Theater in 1977. Hagedorn followed with her own multimedia piece, Tenement Lover: No Palm Trees in New York City, which was produced in 1981 at the Kitchen and directed by Thulani Davis, who also wrote the libretto for her cousin Anthony Davis’s acclaimed opera X: The Life & Times of Malcolm X, which was performed at the Metropolitan Opera in 2023.

Despite its vitality and importance, the multicultural renaissance of the 1970s is still ignored by the American critical establishment, which often behaves like an overseas colony of England or France. Still, it’s recognized in India, China, Europe, and Africa.

While Hagedorn has written multiple novels, her debut, Dogeaters, is what defined her as an artistic risk-taker. She has said,

I wrote down “dogeaters” because the word haunted me; it burned a hole in my brain. And when it came time to really make a decision, I had a long talk with some friends—these were African American writers who were part of my community—and they said, “If you’re afraid of something, don’t shy away from it.” So the idea was to flip the word on its head and use it as a defiant title.

On March 14, 2024, Dogeaters was chosen as one of the country’s Great American Novels by the Atlantic Monthly.

Some trace the beginning of the Asian American renaissance to 1974 with the publication of Aiiieeeee!: An Anthology of Asian American Writers. The editors were Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, and Shawn Wong. So frustrated were the Four Horsemen of Asian American Literature that the title of their book is a scream.

There were no women among the Four Horsemen, but Hagedorn made up for that omission in 1993 by publishing the anthology Charlie Chan Is Dead. She wrote,

Ingrained in American popular culture, Charlie Chan is as much a part of the legacy of cultural stereotypes that continues to haunt, frustrate, and—dare I say it?—sometimes inspire us. Fu Manchu. The bucktoothed, apelike Jap wielding his bayonet. The cunning Dragon Lady. Tokyo Rose. The Placid Geisha. The indolent Filipino House-boy. The Model Minority. Miss Saigon, tragic victim/whore of war-torn Vietnam. Weeping. Giggling, bowing, and scraping. Sexually available, eager to deceive or to please. As of 2003, you can add these stereotypes to the list: the belligerent Korean Grocer, the goofy Japanime Geek, and the campy, innocuous “Charlie’s Angel.” I must confess to a soft spot for kick-ass, kung-fu fightin’ mamas, no matter how preposterous and absurd. Is Charlie Chan really dead? Probably not. According to the critic and scholar David Eng, Charlie’s merely in a coma.

During her panel remarks, Hagedorn said of the San Francisco depicted in The Gangster of Love: “We had fun. It was beautiful and dangerous. We could afford to live here, with little rent and utilities included.... The Chicano movement, Asian American, and Black Power—it hit me like a ton of bricks.”•

Join us on April 18 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when Hagedorn will appear in conversation with CBC host John Freeman and a special guest to discuss The Gangster of Love. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

Ishmael Reed’s latest novel is The Terrible Fours. He is a Distinguished Professor at California College of the Arts.