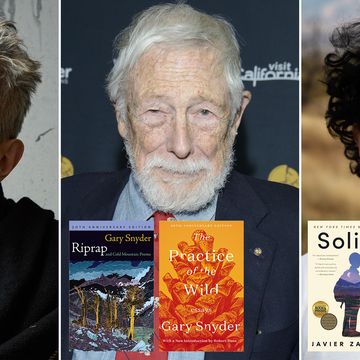

In October 1955, in a pivotal moment for the San Francisco Renaissance, the poet Kenneth Rexroth introduced several poets who had come to read at the Six Gallery, which was set up in a converted auto repair shop on 3119 Fillmore in San Francisco. The poets were Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, and Philip Whalen. Snyder had to read last—after Ginsberg publicly read “Howl” for the first time and shook the listeners. That reading was crucial for Ginsberg and the city’s avant-garde, but it was also part of a larger period that was important to Snyder specifically. Snyder read “A Berry Feast,” a poem he’d written the summer before while working on a trail crew in Yosemite National Park. It was one of a series of poems that he regarded as the start of his life as a poet, even though he’d written poems for 10 years previously. During college, Snyder had written poems that echoed “Yeats, Eliot, Pound, Williams, and Stevens,” but he threw them out when he was 25.

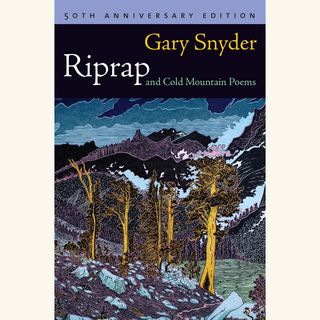

The year after the Six Gallery reading, Snyder went traveling and continued to write the poems that appear in his collection Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems, which includes both his own poems and his translations of Chinese poet Han-shan’s work. Initially, Riprap was published as a stand-alone collection in Japan in 1959, just before Snyder would enter his thirties. Over the four-year period from reading “A Berry Feast” at Six Gallery, a poem about a tribal celebration that includes some cluttered Beat-style lines, to the publication of the best poems in Riprap, Snyder found a unique footing as a poet.

However, a number of the Riprap poems still seem to fall under the influence of the imagist poets, particularly William Carlos Williams, who had influenced a number of San Francisco Renaissance poets. One of the principles of imagist poetry was to give direct treatment to things, and this kind of aesthetic choice also seems to undergird some of Snyder’s poems in Riprap. For instance, Snyder’s brief poem “All Through the Rains” starts with “That mare stood in the field— / A big pine tree and a shed, / But she stayed in open / Ass to the wind, splash wet.” It uses the colloquial or vernacular voice and simple, mostly unornamented or descriptive imagery of Williams’s poems. For Williams, it was important to work from the local: the ordinary, the surroundings, what was actually experienced; in “This Is Just to Say,” he closes with the simple “Forgive me / they were delicious / so sweet / and so cold.” In “All Through the Rains,” the speaker tries to catch the horse to ride her bareback, an infraction not unlike eating the plums Williams alludes to, but the horse simply bolts and leaves to eat in the shade.

But unlike Williams, Snyder wasn’t interested in working only from the local and ordinary, or not in the obvious way. He perceived what was local differently. From poem to poem, Snyder moves us between what might be considered “local” in the United States and what is local to him once he starts traveling around the Pacific Rim. In other words, Snyder tries to reconcile his impulse toward unassuming language about the West in which he grew up with his curiosity about spiritualities and Eastern images that must have been strikingly unfamiliar when he encountered them in his twenties; academic study doesn’t prepare a traveler for actual experience of a country. And the structure of the collection is peripatetic—as was he in the years during which he wrote the poems.

Take Snyder’s poem “Nooksack Valley,” which he dated February 1956—he was 25 years old that month. He begins by talking about a trip north to a berry picker’s cabin, with an emphasis on direct images—the heron flapping by, a setter pup napping, farms among the bends in the Nooksack River in northwestern Washington. In his mind, perhaps, he travels back down Highway 99 to “San Francisco and Japan.” Snyder would later call himself a Pacific Rim poet, making explicit the connection he feels between the West Coast and East Asian countries, but at the time he wrote this phrase, “San Francisco and Japan,” readers must have found it delightfully unexpected and free—the imagining of a seamless route from Highway 99 in Washington down to the coast and then over to Japan. There is a feeling in that line, still, of Snyder’s sense that there is a deep connectedness between places that are miles away from each other.

The poem after the next one in the collection is “TŌJI,” and it’s set at “Shingon temple, Kyoto.” In this one, Snyder tries to use the local and vernacular to write about the scene at the temple. It opens, again, with the plain: “Men asleep in their underwear / Newspapers under their heads.” But then it moves to what likely felt unusual, a little wondrous, to Snyder the first time he saw them, gold-leaf statues of gods and their expressions. At this early point in his life as a young poet and seeker, Snyder hasn’t fully hit his stride or fused his being with these different landscapes. Yet, this poem closes, like many of his poems since, in a lovely, understated way: “Nobody bothers you in Tōji; / The streetcar clanks by outside.”•

Join us on May 16 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when an array of panelists and CBC host John Freeman, with an appearance by Snyder, will gather to discuss Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems and The Practice of the Wild. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

EXCERPT

Read the title poem of Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems, then pick up the book and read them all. —Alta

“ORDERING OF IMPERMANENCE”

Read a beautiful essay by environmental historian and author Daegan Miller (This Radical Land) on the entwining of language and wilderness in The Practice of the Wild. —Alta

WHY I WRITE

Poet and essayist Gary Snyder writes by turning off “the calculating mind.” —Alta

WHY READ THIS

Alta Journal books editor David L. Ulin recommends Snyder’s work, calling it “a gesture of generosity.” —Alta

RECONFIGURING THE FAMILY SAGA

Author and critic Ilana Masad reviews Rachel Khong’s Real Americans, a sprawling novel about three generations of a family that considers the perspectives and circumstances that shape the characters’ choices. —Alta

ACTION OF IDEAS

CBC host John Freeman interviewed author Viet Thanh Nguyen (A Man of Two Faces) for the recent print issue of Alta Journal. Freeman says, “Nguyen may be one of the most revolutionary thinkers in America.” —Alta

Alta’s California Book Club email newsletter is published weekly. Sign up for free and you also will receive four custom-designed bookplates.

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.